Michael Charland

Swift Developer

GitHub Pull Request Evolution

Published Apr 01, 2020

While I was at previous employer how we used GitHub Pull Requests(PR) drastically changed from a non-important step to becoming a critical, helpful, and insightful one. This is a recap of how that happened.

The Beginning

When I started on the iOS team in December of 2017 PRs had no required build checks. The only build check was a Jenkins build of the project that passed intermittently. And failed a lot and no one knew why mostly because no one really knew how it worked. When working with Jenkins it felt like the following:

Discovery

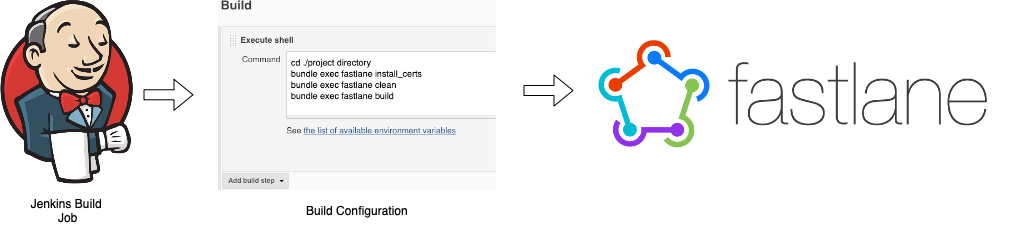

I have worked with Jenkins in the past and have seen how it can greatly help a team gain confidence in there code base. I wanted my team new to have that confidence so I began my investigation into discovering how the whole build process worked. This involved learning how in the Jenkins execute shell it was directly calling the Fastlane commands and how anybody could go in and change the steps (Which they did).

This was bad as we had no idea what a good copy of the execute shell steps looked like. Developers would complain that the build didn’t work, go in, hack the commands, and get mad that it just didn’t work. This had to get better.

Infrastructure as Code

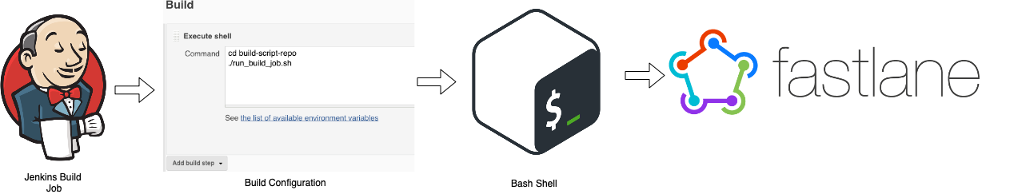

Talking it over with a DevOps engineer he suggested pulling out the script into its own Git repository. The Git repository would also hold scripts for Android, Web, and backend. For iOS, Jenkins would now just call the Bash script to build the project.

This was an easy early win putting the build scripts under change control. Now people couldn’t go through and make unseen changes, removing one variable of uncertainty. This also made the DevOps code use a PR review process allowing for more shared knowledge and we were also able to rely on the expertise of the DevOps team when making build related changes.

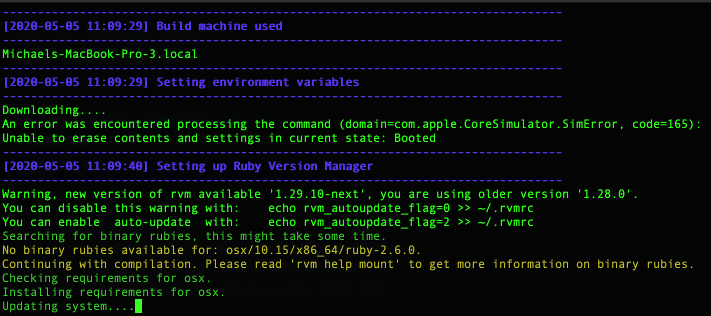

Clean Up

The next step was to make it obvious in the script what each step was doing and having it print helpful information to the console. After this was done, the build would be more informative and debuggable. We agreed as a team to make it a required build check. We also had some unit tests that weren’t being run because they were flaky, so I identified any of these tests and disabled or fixed them. Then the unit tests became a mandatory build check. We now had a stable build with unit tests and when the build failed it was a lot more obvious why. Here is a sample of what the output looked like.

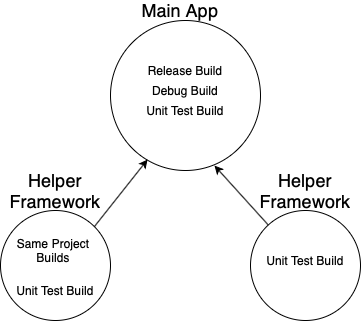

Helper Frameworks

Next our attention turned to also building the helper frameworks. We didn’t just have one massive project, but three projects. The two helper projects needed some love and care to get them to being reliable enough to being a mandatory build check. They also had some flaky unit tests which were fixed or removed. This was the same process as for the main project of cleaning up the scripts to stabilize the build. We now had 6 mandatory build checks as shown below This really helped stabilize our code base.

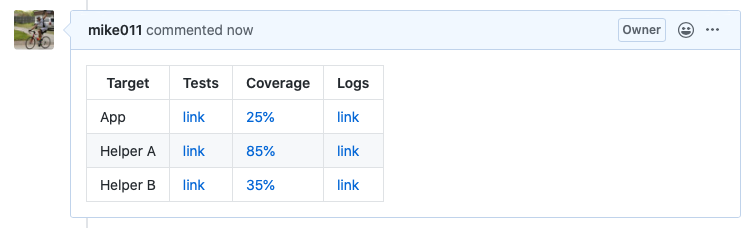

GitHub Comments

We now had numerous jobs running on each PR and it was difficult when the build failed to investigate why it did. This was because the output was hard to find or missing. So I focused on making the PR have as much helpful information in it as possible. This included storing logs, adding links to log files, build artifacts, test results, and to code coverage reports. This made it easier and more obvious what went wrong. This was an ever evolving process to make the build output. We now had a stable build of the main app and its frameworks with helpful links to build related information. This also made build failure investigating easier having more pertinent information present.

Error Reporting

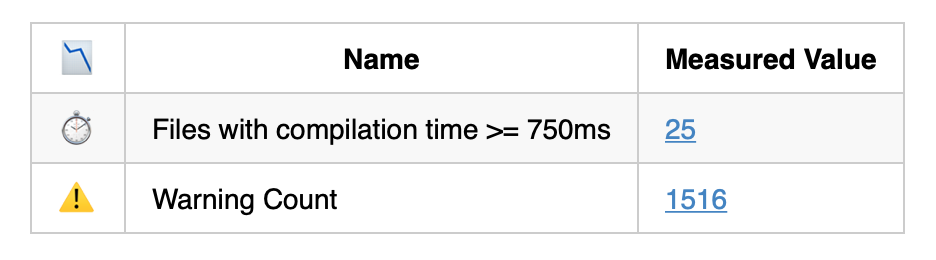

Next we turned our attention to quality of the code we were writing. The first thing we tackled was warnings. We had tens of thousands of them. This made is we would ignore all warnings when developing and after being burnt on this numerous times an effort was put forward to reduce the warnings. One of the senior developers went through and logged a bunch of investigation Jira tickets of the major categories of the warnings. The ideas was we would pick these up overtime and see how hard it was to fix the warnings in the category. If it was easy we would just fix the warnings in the ticket, if not a new ticket was spun off with a description of how much work it would be to fix the warnings. This was a great approach as it shared the load and we got the warnings down to under a thousand. Another developer then made it so the amount of warnings showed up in each PR. This helped give the team an idea of how many warnings we had and how they were trending. Next in a similar manner the amount of warnings from the linter were handled. Finally we formatted the whole code base using SwiftFormat. We now had cleaner code with less warnings.

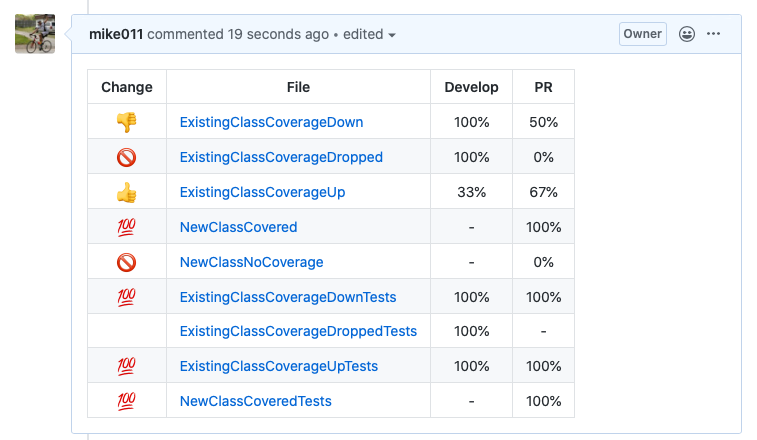

Code Coverage Improvements

For each Pull Request we had a report that contained the amount of code coverage, but you would have to dig to find out what the difference with the base branch was. This was annoying, time consuming, and thusly hardly ever done. This became obvious when our code coverage numbers stagnated over multiple quarters. So I put forward an effort to write a Swift MacOS app called Code Coverage Compare. It create an HMTL report of the code coverage changed of each Swift file of the Pull Request. This greatly encouraged developers to write more tests to help improve the coverage. The effect was nearly immediate as our code coverage numbers started to climb again. We now had a solid build with clean code and ever gaining code coverage numbers.

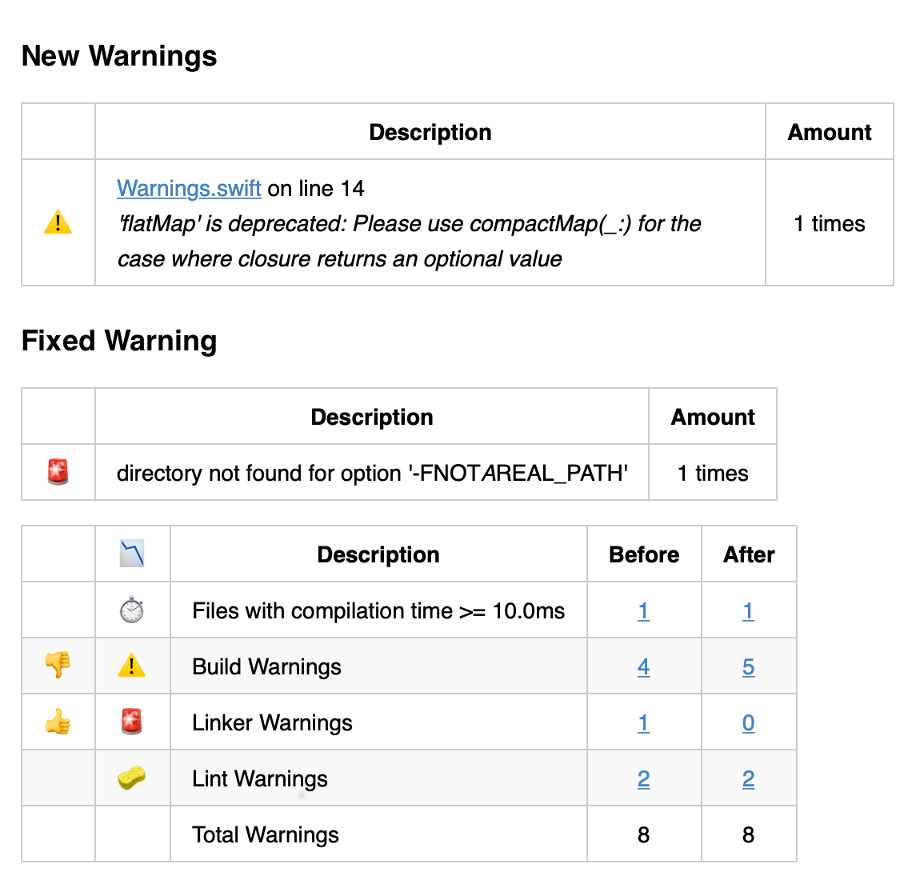

Error Report Improvements

Similar to the code coverage issue I wrote a MacOS app called Post Build Analyzer which would compares all the warnings in the PR versus those in the base branch. This wasn’t just build warnings, but slow to compile files, and lint warnings. This tool created a HTML report showing new warnings added, and warnings fixed. This made it absolutely trivial for developers to see how there code was effecting the code base.

Ands that were things left off for me. There were some other improvements made along the way such as reducing the build time which I didn’t cover in this article. But I might write a short article about how that happened. It’s an interesting tradeoff between building everything and being really expensive, and building just the right amount, but not over complicating things, and being to cheap.

The End

So in summary we moved from a state of the build checks on Pull Requests being useless, to them providing a rich amount of useful and helpful information. This helped drive up the quality and consistency of the builds, the code quality, the code coverage, reduced build related headaches, and made for happier developers.

Thank you for reading this article. Have a great day.